2025-07-14 20:17:00

Diana Engelmann

Filip Shatlan

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-15

2025-07-14 23:18:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-19

2025-07-14 11:19:00

Zack Wettstein

Seattle, United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-07-14 20:05:00

Svalbard

Longyearbyen, Svalbard

Svalbard

NOAA-19

2025-07-14 12:24:00

Diana Engelmann

Filip Shatlan

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-18

2025-07-14 21:21:00

Oppressive Heat Project

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Cambodia

NOAA-19

2025-07-14 09:03:00

Maufox

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-19

2025-07-13 23:56:00

Diana Engelmann

Filip Shatlan

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-18

2025-07-13 19:30:00

Zack Wettstein

Seattle, United States

United States

NOAA-15

2025-07-13 12:37:00

Diana Engelmann

Filip Shatlan

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-18

2025-07-13 11:08:00

Gilboa, New York

Gilboa, New York, United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-07-13 16:54:00

Svalbard

Longyearbyen, Svalbard

Svalbard

NOAA-15

2025-07-13 12:04:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-19

2025-07-13 09:16:00

Maufox

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-19

2025-07-12 22:45:00

Diana Engelmann

Filip Shatlan

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-07-13 07:08:00

Oppressive Heat Project

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Cambodia

NOAA-15

2025-07-12 19:32:00

Gilboa, New York

Gilboa, New York, United States

United States

NOAA-15

2025-07-12 11:44:00

Zack Wettstein

Seattle, United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-07-12 11:25:00

Diana Engelmann

Filip Shatlan

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-07-12 21:46:00

Oppressive Heat Project

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Cambodia

NOAA-19

2025-07-12 13:48:00

Svalbard

Longyearbyen, Svalbard

Svalbard

NOAA-19

2025-07-12 12:17:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-19

2025-07-12 09:28:00

Maufox

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-19

2025-07-11 22:57:00

Diana Engelmann

Filip Shatlan

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-07-11 08:59:00

Zack Wettstein

Seattle, United States

United States

NOAA-15

2025-07-11 11:38:00

Diana Engelmann

Filip Shatlan

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-07-11 08:38:00

Gilboa, New York

Gilboa, New York, United States

United States

NOAA-15

2025-07-11 19:04:00

Oppressive Heat Project

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Cambodia

NOAA-15

2025-07-11 11:07:00

Svalbard

Longyearbyen, Svalbard

Svalbard

NOAA-15

2025-07-11 09:37:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-15

2025-07-11 09:41:00

Maufox

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-19

2025-07-10 21:58:00

Zack Wettstein

Seattle, United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-07-10 23:10:00

Diana Engelmann

Filip Shatlan

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-07-10 20:22:00

Diana Engelmann

Filip Shatlan

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-15

2025-07-10 19:15:00

Svalbard

Longyearbyen, Svalbard

Svalbard

NOAA-19

2025-07-10 11:46:00

Gilboa, New York

Gilboa, New York, United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-07-10 12:43:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-19

2025-07-10 09:53:00

Maufox

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-19

2025-07-09 22:11:00

Zack Wettstein

Seattle, United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-07-09 23:23:00

Diana Engelmann

Filip Shatlan

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-07-10 06:47:00

Oppressive Heat Project

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Cambodia

NOAA-15

2025-07-09 19:11:00

Gilboa, New York

Gilboa, New York, United States

United States

NOAA-15

2025-07-09 20:09:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-15

2025-07-09 19:28:00

Svalbard

Longyearbyen, Svalbard

Svalbard

NOAA-19

2025-07-09 12:03:00

Diana Engelmann

Filip Shatlan

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-07-09 10:06:00

Maufox

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-19

2025-07-09 08:10:00

Cyprus Amateur Radio Society

Nicosia , Cyprus

Cyprus

NOAA-15

2025-07-08 23:21:00

Diana Engelmann

Filip Shatlan

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-18

2025-07-08 21:57:00

Gilboa, New York

Gilboa, New York, United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-07-09 07:13:00

Oppressive Heat Project

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Cambodia

NOAA-15

2025-07-08 22:09:00

Cyprus Amateur Radio Society

Nicosia , Cyprus

Cyprus

NOAA-19

2025-07-08 12:01:00

Diana Engelmann

Filip Shatlan

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-18

2025-07-08 08:38:00

Zack Wettstein

Seattle, United States

United States

NOAA-15

2025-07-08 10:46:00

Svalbard

Longyearbyen, Svalbard

Svalbard

NOAA-15

2025-07-08 09:16:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-15

2025-07-08 10:19:00

Maufox

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-19

2025-07-08 09:46:00

Oppressive Heat Project

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Cambodia

NOAA-19

2025-07-07 22:10:00

Gilboa, New York

Gilboa, New York, United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-07-07 20:00:00

Diana Engelmann

Filip Shatlan

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-15

2025-07-07 23:06:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-19

2025-07-07 09:04:00

Zack Wettstein

Seattle, United States

United States

NOAA-15

2025-07-07 08:47:00

Diana Engelmann

Filip Shatlan

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-15

2025-07-07 11:12:00

Svalbard

Longyearbyen, Svalbard

Svalbard

NOAA-15

2025-07-07 10:59:00

Cyprus Amateur Radio Society

Nicosia , Cyprus

Cyprus

NOAA-19

2025-07-07 10:32:00

Maufox

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-19

2025-07-07 09:59:00

Oppressive Heat Project

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Cambodia

NOAA-19

2025-07-06 22:23:00

Gilboa, New York

Gilboa, New York, United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-07-06 23:18:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-19

2025-07-06 11:19:00

Zack Wettstein

Seattle, United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-07-06 16:37:00

Svalbard

Longyearbyen, Svalbard

Svalbard

NOAA-15

2025-07-06 21:22:00

Oppressive Heat Project

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Cambodia

NOAA-19

2025-07-06 11:12:00

Cyprus Amateur Radio Society

Nicosia , Cyprus

Cyprus

NOAA-19

2025-07-06 09:04:00

Maufox

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-19

2025-07-05 11:32:00

Zack Wettstein

Seattle, United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-07-05 11:09:00

Gilboa, New York

Gilboa, New York, United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-07-05 17:03:00

Svalbard

Longyearbyen, Svalbard

Svalbard

NOAA-15

2025-07-05 21:34:00

Oppressive Heat Project

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Cambodia

NOAA-19

2025-07-05 12:05:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-19

2025-07-05 09:16:00

Maufox

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-19

2025-07-05 08:15:00

Cyprus Amateur Radio Society

Nicosia , Cyprus

Cyprus

NOAA-15

2025-07-04 20:17:00

Svalbard

Longyearbyen, Svalbard

Svalbard

NOAA-18

2025-07-04 08:43:00

Zack Wettstein

Seattle, United States

United States

NOAA-15

2025-07-04 08:21:00

Gilboa, New York

Gilboa, New York, United States

United States

NOAA-15

2025-07-04 18:47:00

Oppressive Heat Project

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Cambodia

NOAA-15

2025-07-04 12:18:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-19

2025-07-04 08:41:00

Cyprus Amateur Radio Society

Nicosia , Cyprus

Cyprus

NOAA-15

2025-07-04 09:29:00

Maufox

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-19

2025-07-03 21:32:00

Cyprus Amateur Radio Society

Nicosia , Cyprus

Cyprus

NOAA-19

2025-07-03 20:30:00

Svalbard

Longyearbyen, Svalbard

Svalbard

NOAA-18

2025-07-03 09:09:00

Zack Wettstein

Seattle, United States

United States

NOAA-15

2025-07-03 08:47:00

Gilboa, New York

Gilboa, New York, United States

United States

NOAA-15

2025-07-03 19:13:00

Oppressive Heat Project

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Cambodia

NOAA-15

2025-07-03 12:31:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-19

2025-07-03 09:41:00

Maufox

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-19

2025-07-02 21:59:00

Zack Wettstein

Seattle, United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-07-02 23:11:00

Diana Engelmann

Filip Shatlan

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-07-02 19:16:00

Svalbard

Longyearbyen, Svalbard

Svalbard

NOAA-19

2025-07-02 19:10:00

Cyprus Amateur Radio Society

Nicosia , Cyprus

Cyprus

NOAA-15

2025-07-02 11:52:00

Diana Engelmann

Filip Shatlan

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-07-02 11:47:00

Gilboa, New York

Gilboa, New York, United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-07-02 11:45:00

Goownown Growers

The Seaweed Institute

CAST, Helston, Cornwall, United Kingdom

United Kingdom

NOAA-19

2025-07-02 12:43:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-19

2025-07-02 09:54:00

Maufox

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-19

2025-07-01 22:11:00

Zack Wettstein

Seattle, United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-07-02 06:56:00

Oppressive Heat Project

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Cambodia

NOAA-15

2025-07-01 19:20:00

Gilboa, New York

Gilboa, New York, United States

United States

NOAA-15

2025-07-01 20:19:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-15

2025-07-01 12:04:00

Diana Engelmann

Filip Shatlan

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-07-01 17:08:00

Svalbard

Longyearbyen, Svalbard

Svalbard

NOAA-15

2025-07-01 11:58:00

Goownown Growers

The Seaweed Institute

CAST, Helston, Cornwall, United Kingdom

United Kingdom

NOAA-19

2025-07-01 10:07:00

Maufox

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-19

2025-07-01 08:20:00

Cyprus Amateur Radio Society

Nicosia , Cyprus

Cyprus

NOAA-15

2025-06-30 23:23:00

Diana Engelmann

Filip Shatlan

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-18

2025-07-01 07:22:00

Oppressive Heat Project

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Cambodia

NOAA-15

2025-06-30 23:28:00

Goownown Growers

The Seaweed Institute

CAST, Helston, Cornwall, United Kingdom

United Kingdom

NOAA-18

2025-06-30 22:10:00

Cyprus Amateur Radio Society

Nicosia , Cyprus

Cyprus

NOAA-19

2025-06-30 08:31:00

Diana Engelmann

Filip Shatlan

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-15

2025-06-30 08:26:00

Gilboa, New York

Gilboa, New York, United States

United States

NOAA-15

2025-06-30 10:55:00

Svalbard

Longyearbyen, Svalbard

Svalbard

NOAA-15

2025-06-30 09:25:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-15

2025-06-30 10:20:00

Maufox

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-19

2025-06-30 09:47:00

Oppressive Heat Project

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Cambodia

NOAA-19

2025-06-29 22:11:00

Gilboa, New York

Gilboa, New York, United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-06-29 20:10:00

Diana Engelmann

Filip Shatlan

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-15

2025-06-29 22:13:00

Goownown Growers

The Seaweed Institute

CAST, Helston, Cornwall, United Kingdom

United Kingdom

NOAA-19

2025-06-29 23:07:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-19

2025-06-29 08:56:00

Diana Engelmann

Filip Shatlan

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-15

2025-06-29 11:00:00

Cyprus Amateur Radio Society

Nicosia , Cyprus

Cyprus

NOAA-19

2025-06-29 10:33:00

Maufox

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-19

2025-06-28 23:49:00

Diana Engelmann

Filip Shatlan

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-18

2025-06-29 10:00:00

Oppressive Heat Project

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Cambodia

NOAA-19

2025-06-28 22:26:00

Goownown Growers

The Seaweed Institute

CAST, Helston, Cornwall, United Kingdom

United Kingdom

NOAA-19

2025-06-28 12:29:00

Diana Engelmann

Filip Shatlan

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-18

2025-06-28 19:14:00

Cyprus Amateur Radio Society

Nicosia , Cyprus

Cyprus

NOAA-15

2025-06-28 10:57:00

Gilboa, New York

Gilboa, New York, United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-06-28 14:52:00

Svalbard

Longyearbyen, Svalbard

Svalbard

NOAA-18

2025-06-28 11:53:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-19

2025-06-28 09:05:00

Maufox

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-19

2025-06-27 22:34:00

Diana Engelmann

Filip Shatlan

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-06-28 07:01:00

Oppressive Heat Project

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Cambodia

NOAA-15

2025-06-27 19:24:00

Gilboa, New York

Gilboa, New York, United States

United States

NOAA-15

2025-06-27 12:42:00

Diana Engelmann

Filip Shatlan

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-18

2025-06-27 21:35:00

Oppressive Heat Project

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Cambodia

NOAA-19

2025-06-27 12:36:00

Goownown Growers

The Seaweed Institute

CAST, Helston, Cornwall, United Kingdom

United Kingdom

NOAA-18

2025-06-27 12:06:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-19

2025-06-27 08:24:00

Cyprus Amateur Radio Society (CY)

Nicosia , Cyprus

Cyprus

NOAA-15

2025-06-27 09:17:00

Maufox

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-19

2025-06-26 22:46:00

Diana Engelmann

Filip Shatlan

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-06-26 11:26:00

Diana Engelmann

Filip Shatlan

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-06-26 18:56:00

Oppressive Heat Project (KH)

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Cambodia

NOAA-15

2025-06-26 12:49:00

Goownown Growers

The Seaweed Institute

CAST, Helston, Cornwall, United Kingdom

United Kingdom

NOAA-18

2025-06-26 12:19:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-19

2025-06-26 09:29:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-15

2025-06-26 08:50:00

Cyprus Amateur Radio Society (CY)

Nicosia , Cyprus

Cyprus

NOAA-15

2025-06-26 09:30:00

Maufox (MU)

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-19

2025-06-25 22:59:00

Diana Engelmann

Filip Shatlan

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-06-25 20:14:00

Diana Engelmann

Filip Shatlan

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-15

2025-06-25 23:45:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-18

2025-06-25 21:56:00

JHB (SA)

Roodepoort, Johannesburg, South Africa

South Africa

NOAA-19

2025-06-25 21:33:00

Cyprus Amateur Radio Society (CY)

Nicosia , Cyprus

Cyprus

NOAA-19

2025-06-25 22:01:00

Oppressive Heat Project (KH)

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Cambodia

NOAA-19

2025-06-25 13:02:00

Goownown Growers

The Seaweed Institute

CAST, Helston, Cornwall, United Kingdom

United Kingdom

NOAA-18

2025-06-24 23:12:00

Diana Engelmann

Filip Shatlan

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-06-24 23:58:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-18

2025-06-24 19:18:00

Cyprus Amateur Radio Society (CY)

Nicosia , Cyprus

Cyprus

NOAA-15

2025-06-24 11:52:00

Diana Engelmann

Filip Shatlan

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-06-24 22:13:00

Oppressive Heat Project (KH)

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Cambodia

NOAA-19

2025-06-24 11:46:00

Goownown Growers

The Seaweed Institute

CAST, Helston, Cornwall, United Kingdom

United Kingdom

NOAA-19

2025-06-24 11:52:00

Cyprus Amateur Radio Society (CY)

Nicosia , Cyprus

Cyprus

NOAA-18

2025-06-24 10:51:00

Oppressive Heat Project (KH)

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Cambodia

NOAA-18

2025-06-23 23:25:00

Diana Engelmann

Filip Shatlan

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-06-23 23:08:00

Tsonami Arte Sonoro (CL)

Valparaiso, Chile

Chile

NOAA-19

2025-06-23 22:57:00

Tsonami Arte Sonoro (CL)

Valparaiso, Chile

Chile

NOAA-18

2025-06-23 20:51:00

Tsonami Arte Sonoro (CL)

Valparaiso, Chile

Chile

NOAA-15

2025-06-23 21:58:00

Cyprus Amateur Radio Society (CY)

Nicosia , Cyprus

Cyprus

NOAA-19

2025-06-23 20:28:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-15

2025-06-23 12:05:00

Diana Engelmann

Filip Shatlan

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-06-23 18:49:00

Maufox (MU)

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-15

2025-06-23 11:58:00

Goownown Growers

The Seaweed Institute

CAST, Helston, Cornwall, United Kingdom

United Kingdom

NOAA-19

2025-06-23 10:08:00

Maufox (MU)

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-19

2025-06-23 11:05:00

Oppressive Heat Project (KH)

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Cambodia

NOAA-18

2025-06-23 06:23:00

Maufox (MU)

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-15

2025-06-22 19:53:00

Diana Engelmann

Filip Shatlan

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-15

2025-06-22 23:30:00

Goownown Growers

The Seaweed Institute

CAST, Helston, Cornwall, United Kingdom

United Kingdom

NOAA-18

2025-06-22 08:40:00

Diana Engelmann

Filip Shatlan

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-15

2025-06-22 19:01:00

Oppressive Heat Project (KH)

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Cambodia

NOAA-15

2025-06-22 12:57:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-18

2025-06-22 10:48:00

Cyprus Amateur Radio Society (CY)

Nicosia , Cyprus

Cyprus

NOAA-19

2025-06-22 10:21:00

Maufox (MU)

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-19

2025-06-22 09:47:00

Oppressive Heat Project (KH)

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Cambodia

NOAA-19

2025-06-21 23:07:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-19

2025-06-21 22:39:00

Oppressive Heat Project (KH)

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Cambodia

NOAA-18

2025-06-21 10:34:00

Maufox (MU)

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-19

2025-06-20 23:51:00

Diana Engelmann

Filip Shatlan

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-18

2025-06-20 23:04:00

Iterable pueyrredon (AR)

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-19

2025-06-20 21:28:00

Iterable pueyrredon (AR)

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-15

2025-06-20 19:49:00

Iterable pueyrredon (AR)

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-15

2025-06-20 12:32:00

Diana Engelmann

Filip Shatlan

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-18

2025-06-20 11:53:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-19

2025-06-20 09:06:00

Maufox (MU)

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-19

2025-06-19 08:33:00

Cyprus Amateur Radio Society (CY)

Nicosia , Cyprus

Cyprus

NOAA-15

2025-06-19 09:18:00

Maufox (MU)

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-19

2025-06-18 22:47:00

Diana Engelmann

Filip Shatlan

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-06-18 23:29:00

Iterable pueyrredon (AR)

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-19

2025-06-18 20:40:00

Iterable pueyrredon (AR)

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-15

2025-06-18 22:50:00

Cyprus Amateur Radio Society (CY)

Nicosia , Cyprus

Cyprus

NOAA-18

2025-06-18 11:27:00

Diana Engelmann

Filip Shatlan

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-06-18 11:23:00

Gilboa, New York (US)

Gilboa, New York, United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-06-06 06:51:00

Louis Potgieter

Roodepoort, Johannesburg, South Africa

South Africa

NOAA-15

2025-06-05 19:39:00

Louis Potgieter

Roodepoort, Johannesburg, South Africa

South Africa

NOAA-15

2025-06-15 22:10:00

Louis Potgieter

Roodepoort, Johannesburg, South Africa

South Africa

NOAA-19

2025-06-18 19:05:00

Oppressive Heat Project (KH)

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Cambodia

NOAA-15

2025-06-18 12:47:00

Goownown Growers

The Seaweed Institute

CAST, Helston, Cornwall, United Kingdom

United Kingdom

NOAA-18

2025-06-18 08:20:00

Iterable pueyrredon (AR)

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-15

2025-06-18 12:19:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-19

2025-06-17 23:18:00

Zack Wettstein (US)

Seattle, United States

United States

NOAA-18

2025-06-18 09:30:00

Maufox (MU)

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-19

2025-06-17 22:59:00

Diana Engelmann

Filip Shatlan

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-06-17 22:51:00

Gilboa, New York (US)

Gilboa, New York, United States

United States

NOAA-18

2025-06-17 23:42:00

Iterable pueyrredon (AR)

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-19

2025-06-17 21:06:00

Iterable pueyrredon (AR)

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-15

2025-06-17 23:47:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-18

2025-06-17 23:03:00

Cyprus Amateur Radio Society (CY)

Nicosia , Cyprus

Cyprus

NOAA-18

2025-06-17 11:40:00

Diana Engelmann

Filip Shatlan

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-06-17 11:05:00

Iterable pueyrredon (AR)

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-18

2025-06-17 09:03:00

Goownown Growers

The Seaweed Institute

CAST, Helston, Cornwall, United Kingdom

United Kingdom

NOAA-15

2025-06-17 09:43:00

Maufox (MU)

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-19

2025-06-17 10:41:00

Oppressive Heat Project (KH)

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Cambodia

NOAA-18

2025-06-16 23:12:00

Diana Engelmann

Filip Shatlan

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-06-16 23:05:00

Gilboa, New York (US)

Gilboa, New York, United States

United States

NOAA-18

2025-06-16 22:56:00

Tsonami Arte Sonoro (CL)

Valparaiso, Chile

Chile

NOAA-19

2025-06-16 23:55:00

Iterable pueyrredon (AR)

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-19

2025-06-16 22:47:00

Tsonami Arte Sonoro (CL)

Valparaiso, Chile

Chile

NOAA-18

2025-06-16 19:37:00

Zack Wettstein (US)

Seattle, United States

United States

NOAA-15

2025-06-17 10:13:00

Jo Pollitt

Rumen Rachev

Perth , Australia

Australia

NOAA-18

2025-06-16 21:35:00

Gilboa, New York (US)

Gilboa, New York, United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-06-16 20:34:00

Tsonami Arte Sonoro (CL)

Valparaiso, Chile

Chile

NOAA-15

2025-06-16 19:13:00

Gilboa, New York (US)

Gilboa, New York, United States

United States

NOAA-15

2025-06-16 20:11:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-15

2025-06-16 19:28:00

Cyprus Amateur Radio Society (CY)

Nicosia , Cyprus

Cyprus

NOAA-15

2025-06-16 12:01:00

Tsonami Arte Sonoro (CL)

Valparaiso, Chile

Chile

NOAA-18

2025-06-16 11:53:00

Diana Engelmann

Filip Shatlan

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-06-16 11:18:00

Iterable pueyrredon (AR)

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-18

2025-06-16 11:42:00

Goownown Growers

The Seaweed Institute

CAST, Helston, Cornwall, United Kingdom

United Kingdom

NOAA-19

2025-06-16 07:33:00

Iterable pueyrredon (AR)

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-15

2025-06-16 09:56:00

Maufox (MU)

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-19

2025-06-15 22:14:00

Zack Wettstein (US)

Seattle, United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-06-15 23:17:00

Gilboa, New York (US)

Gilboa, New York, United States

United States

NOAA-18

2025-06-15 23:00:00

Tsonami Arte Sonoro (CL)

Valparaiso, Chile

Chile

NOAA-18

2025-06-15 23:57:00

Iterable pueyrredon (AR)

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-18

2025-06-16 10:25:00

Jo Pollitt

Rumen Rachev

Perth , Australia

Australia

NOAA-18

2025-06-15 21:00:00

Tsonami Arte Sonoro (CL)

Valparaiso, Chile

Chile

NOAA-15

Son las 11 de la noche y cae la lluvia más intensa del año sobre Valparaíso. Desde mi ventana veo las colinas del cerro del frente y una calle inundada con un río de agua bajando la quebrada. Una bruma acompaña el ruido uniforme de la lluvia, iluminada por los faroles de la calle. La ciudad está silente y vacía, tomada por el agua que cae y su suave sonido.

2025-06-16 07:14:00

Oppressive Heat Project (KH)

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Cambodia

NOAA-15

2025-06-15 19:38:00

Gilboa, New York (US)

Gilboa, New York, United States

United States

NOAA-15

2025-06-15 12:15:00

Zack Wettstein (US)

Seattle, United States

United States

NOAA-18

2025-06-15 21:59:00

Cyprus Amateur Radio Society (CY)

Nicosia , Cyprus

Cyprus

NOAA-19

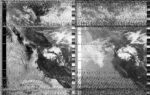

It was a typical warm June day with a clear sky. The temperature high was around 37 degrees celcius. In general it was a good day. At the time the picture was taken a couple kids could be heard having fun in their backyard. A couple of neighbours ware also observed taking a late afternoon walk, as the temperature had subsided to about 24 degrees celcius.

2025-06-15 20:37:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-15

2025-06-15 12:06:00

Diana Engelmann

Filip Shatlan

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-06-15 08:40:00

Zack Wettstein (US)

Seattle, United States

United States

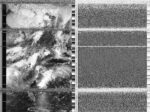

NOAA-15

This morning pass of NOAA-15 captured by the Seattle AGS highlights the clear skies above the Puget Sound region, where we've experienced a few days of respite after a record-setting heat wave in early June. The high pressure system that is currently contributing to the comfortable temperature and cloudless skies is also helping keep the Canadian wildfire smoke at bay and out of the region for the most part, which cannot be said for the Midwest and Eastern US where the plumes and particulate have been blowing for weeks.

2025-06-15 11:31:00

Iterable pueyrredon (AR)

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-18

2025-06-15 08:23:00

Diana Engelmann

Filip Shatlan

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-15

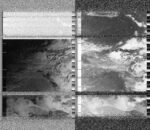

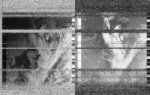

It was a truly remarkable day in my neighborhood this Sunday, as if the weather itself knew that NOAA 18 and 19 would send their final signals. We had our first summer storm since Friday in a typical central Florida pattern - sunshine and heat, followed by sudden clouds and patches of rain.

I love summer storms in Gainesville because they feel the same as summer storms on the island of Hvar in Croatia. As shown in these photos, one begins to walk down the street under perfect blue sky, and just thirty minutes later, the first innocent puffs of white clouds travel above, followed soon by their older, grayer and heavier companions. And then, for a brief moment, all the birds and cicadas are suddenly quiet, before the first sounds of thunder in the distance. Ancient oaks with their Spanish moss lace and tall pines among patiently wait for the first drops of rain.

2025-06-15 08:18:00

Gilboa, New York (US)

Gilboa, New York, United States

United States

NOAA-15

Misty day today. Atmospheric and cozy, though I do find myself wanting to see into the distance and the open sky. Antenna tree is fully leafy now here in late spring. Is the antenna a sort of imposter leaf, handling a different part of the EM spectrum from the tree leaves?

2025-06-15 18:44:00

Oppressive Heat Project (KH)

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Cambodia

NOAA-15

2025-06-15 07:59:00

Iterable pueyrredon (AR)

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-15

2025-06-15 11:55:00

Goownown Growers

The Seaweed Institute

CAST, Helston, Cornwall, United Kingdom

United Kingdom

NOAA-19

2025-06-15 11:52:00

Hospitalfield (UK)

Arbroath, Scotland

Scotland

NOAA-19

2025-06-14 23:58:00

Zack Wettstein (US)

Seattle, United States

United States

NOAA-18

2025-06-15 10:09:00

Maufox (MU)

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-19

2025-06-14 22:26:00

Zack Wettstein (US)

Seattle, United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-06-14 23:32:00

Gilboa, New York (US)

Gilboa, New York, United States

United States

NOAA-18

2025-06-15 10:38:00

Jo Pollitt

Rumen Rachev

Perth , Australia

Australia

NOAA-18

what to do with disappearance . . ... > when white noise is pervasive, skies are unshared, what of this repeated body of noise, resonant, insistent, what of this resistance / / . . . } - /\

2025-06-14 22:01:00

Gilboa, New York (US)

Gilboa, New York, United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-06-14 18:50:00

Zack Wettstein (US)

Seattle, United States

United States

NOAA-15

2025-06-14 20:07:00

Gilboa, New York (US)

Gilboa, New York, United States

United States

NOAA-15

2025-06-14 20:03:00

Diana Engelmann

Filip Shatlan

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-15

2025-06-14 20:45:00

Iterable pueyrredon (AR)

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-15

2025-06-14 23:29:00

Goownown Growers

The Seaweed Institute

CAST, Helston, Cornwall, United Kingdom

United Kingdom

NOAA-18

2025-06-14 21:58:00

Hospitalfield (UK)

Arbroath, Scotland

Scotland

NOAA-19

2025-06-14 12:28:00

Zack Wettstein (US)

Seattle, United States

United States

NOAA-18

2025-06-14 22:11:00

Cyprus Amateur Radio Society (CY)

Nicosia , Cyprus

Cyprus

NOAA-19

2025-06-14 22:30:00

Oppressive Heat Project (KH)

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Cambodia

NOAA-18

2025-06-14 23:18:00

Jo Pollitt

Rumen Rachev

Perth , Australia

Australia

NOAA-18

2025-06-14 11:43:00

Iterable pueyrredon (AR)

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-18

2025-06-14 10:13:00

Iterable pueyrredon (AR)

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-19

2025-06-14 08:49:00

Diana Engelmann

Filip Shatlan

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-15

2025-06-14 13:00:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-18

2025-06-14 10:22:00

Maufox (MU)

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-19

2025-06-13 22:52:00

Iterable pueyrredon (AR)

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-19

2025-06-13 23:08:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-19

2025-06-13 12:40:00

Zack Wettstein (US)

Seattle, United States

United States

NOAA-18

2025-06-13 12:22:00

Diana Engelmann

Filip Shatlan

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-18

2025-06-13 22:42:00

Oppressive Heat Project (KH)

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Cambodia

NOAA-18

2025-06-13 23:30:00

Jo Pollitt

Rumen Rachev

Perth , Australia

Australia

NOAA-18

2025-06-13 11:56:00

Iterable pueyrredon (AR)

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-18

2025-06-13 10:25:00

Iterable pueyrredon (AR)

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-19

2025-06-13 09:07:00

Goownown Growers

The Seaweed Institute

CAST, Helston, Cornwall, United Kingdom

United Kingdom

NOAA-15

2025-06-13 09:04:00

Hospitalfield (UK)

Arbroath, Scotland

Scotland

NOAA-15

2025-06-13 11:01:00

Cyprus Amateur Radio Society (CY)

Nicosia , Cyprus

Cyprus

NOAA-19

2025-06-13 10:35:00

Maufox (MU)

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-19

2025-06-12 23:05:00

Iterable pueyrredon (AR)

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-19

2025-06-13 09:33:00

Jo Pollitt

Rumen Rachev

Perth , Australia

Australia

NOAA-19

2025-06-12 19:18:00

Gilboa, New York (US)

Gilboa, New York, United States

United States

NOAA-15

2025-06-12 22:23:00

Goownown Growers

The Seaweed Institute

CAST, Helston, Cornwall, United Kingdom

United Kingdom

NOAA-19

2025-06-12 11:22:00

Zack Wettstein (US)

Seattle, United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-06-12 19:18:00

Hospitalfield (UK)

Arbroath, Scotland

Scotland

NOAA-15

2025-06-12 12:34:00

Diana Engelmann

Filip Shatlan

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-18

2025-06-12 10:38:00

Iterable pueyrredon (AR)

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-19

2025-06-12 07:38:00

Iterable pueyrredon (AR)

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-15

2025-06-12 11:54:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-19

2025-06-12 08:16:00

Cyprus Amateur Radio Society (CY)

Nicosia , Cyprus

Cyprus

NOAA-15

2025-06-12 09:06:00

Maufox (MU)

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-19

2025-06-12 10:24:00

Asmit Rai

Cosmos Astronomy Club

Pune, India

India

NOAA-19

2025-06-11 22:35:00

Diana Engelmann

Filip Shatlan

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-06-11 23:17:00

Iterable pueyrredon (AR)

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-19

2025-06-12 07:19:00

Oppressive Heat Project (KH)

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Cambodia

NOAA-15

2025-06-11 22:40:00

Cyprus Amateur Radio Society (CY)

Nicosia , Cyprus

Cyprus

NOAA-18

2025-06-11 19:44:00

Goownown Growers

The Seaweed Institute

CAST, Helston, Cornwall, United Kingdom

United Kingdom

NOAA-15

2025-06-11 08:45:00

Zack Wettstein (US)

Seattle, United States

United States

NOAA-15

2025-06-11 11:11:00

Gilboa, New York (US)

Gilboa, New York, United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-06-11 21:36:00

Oppressive Heat Project (KH)

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Cambodia

NOAA-19

2025-06-11 10:51:00

Iterable pueyrredon (AR)

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-19

2025-06-11 19:37:00

Jo Pollitt

Rumen Rachev

Perth , Australia

Australia

NOAA-15

2025-06-11 12:33:00

Hospitalfield (UK)

Arbroath, Scotland

Scotland

NOAA-18

2025-06-11 08:03:00

Iterable pueyrredon (AR)

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-15

2025-06-11 12:07:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-19

2025-06-10 23:08:00

Zack Wettstein

Seattle, United States

United States

NOAA-18

2025-06-11 09:19:00

Maufox (MU)

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-19

2025-06-10 22:31:00

Tsonami Arte Sonoro

Valparaiso, Chile

Chile

NOAA-19

2025-06-10 23:30:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-19

2025-06-11 07:54:00

Cosmos Astronomy Club MIT WPU

Pune, India

India

NOAA-15

2025-06-10 20:49:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-15

2025-06-10 22:53:00

Cyprus Amateur Radio Society

Nicosia , Cyprus

Cyprus

NOAA-18

2025-06-10 22:03:00

Cosmos Astronomy Club MIT WPU

Pune, India

India

NOAA-19

2025-06-10 11:25:00

Heidi Neilson

Gilboa, New York, United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-06-10 21:49:00

Oppressive Heat Project

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Cambodia

NOAA-19

2025-06-10 11:03:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-19

2025-06-10 08:54:00

Filip Shatlan and Diana Engelmann

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-15

2025-06-10 12:50:00

Goownown Growers

The Seaweed Institute

CAST, Helston, Cornwall, United Kingdom

United Kingdom

NOAA-18

2025-06-10 12:46:00

Hospitalfield

Arbroath, Scotland

Scotland

NOAA-18

2025-06-10 12:20:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-19

2025-06-09 23:21:00

Zack Wettstein

Seattle, United States

United States

NOAA-18

2025-06-09 23:00:00

Filip Shatlan and Diana Engelmann

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-06-09 22:55:00

Heidi Neilson

Gilboa, New York, United States

United States

NOAA-18

2025-06-09 23:43:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-19

2025-06-09 20:16:00

Tsonami Arte Sonoro

Valparaiso, Chile

Chile

NOAA-15

2025-06-09 21:16:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-15

2025-06-09 23:50:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-18

2025-06-09 23:06:00

Cyprus Amateur Radio Society

Nicosia , Cyprus

Cyprus

NOAA-18

2025-06-09 22:15:00

Cosmos Astronomy Club MIT WPU

Pune, India

India

NOAA-19

2025-06-09 11:08:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-18

2025-06-09 09:12:00

Goownown Growers

The Seaweed Institute

CAST, Helston, Cornwall, United Kingdom

United Kingdom

NOAA-15

2025-06-09 09:09:00

Hospitalfield

Arbroath, Scotland

Scotland

NOAA-15

2025-06-09 09:44:00

Maufox

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-19

2025-06-09 10:43:00

Oppressive Heat Project

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Cambodia

NOAA-18

2025-06-08 23:08:00

Heidi Neilson

Gilboa, New York, United States

United States

NOAA-18

2025-06-08 23:56:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-19

2025-06-08 23:48:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-18

2025-06-08 19:46:00

Zack Wettstein

Seattle, United States

United States

NOAA-15

2025-06-08 21:43:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-15

2025-06-08 19:23:00

Hospitalfield

Arbroath, Scotland

Scotland

NOAA-15

2025-06-08 20:20:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-15

2025-06-08 11:54:00

Filip Shatlan and Diana Engelmann

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-06-08 11:43:00

Goownown Growers

The Seaweed Institute

CAST, Helston, Cornwall, United Kingdom

United Kingdom

NOAA-19

2025-06-08 09:56:00

Maufox

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-19

2025-06-08 08:21:00

Cyprus Amateur Radio Society

Nicosia , Cyprus

Cyprus

NOAA-15

2025-06-07 22:14:00

Zack Wettstein

Seattle, United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-06-08 10:56:00

Oppressive Heat Project

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Cambodia

NOAA-18

2025-06-08 07:33:00

Cosmos Astronomy Club MIT WPU

Pune, India

India

NOAA-15

2025-06-07 23:18:00

Goownown Growers

The Seaweed Institute

CAST, Helston, Cornwall, United Kingdom

United Kingdom

NOAA-18

2025-06-07 21:59:00

Cyprus Amateur Radio Society

Nicosia , Cyprus

Cyprus

NOAA-19

2025-06-07 11:33:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-18

2025-06-07 08:32:00

Filip Shatlan and Diana Engelmann

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-15

2025-06-07 08:29:00

Heidi Neilson

Gilboa, New York, United States

United States

NOAA-15

2025-06-07 18:53:00

Oppressive Heat Project

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Cambodia

NOAA-15

2025-06-07 08:08:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-15

2025-06-07 11:52:00

Hospitalfield

Arbroath, Scotland

Scotland

NOAA-19

2025-06-07 09:27:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-15

2025-06-07 10:09:00

Maufox

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-19

2025-06-07 11:19:00

Cosmos Astronomy Club MIT WPU

Pune, India

India

NOAA-18

2025-06-06 19:55:00

Tsonami Arte Sonoro

Valparaiso, Chile

Chile

NOAA-15

2025-06-06 20:54:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-15

2025-06-06 23:31:00

Goownown Growers

The Seaweed Institute

CAST, Helston, Cornwall, United Kingdom

United Kingdom

NOAA-18

2025-06-06 21:59:00

Hospitalfield

Arbroath, Scotland

Scotland

NOAA-19

2025-06-06 12:31:00

Zack Wettstein

Seattle, United States

United States

NOAA-18

2025-06-06 22:46:00

Cosmos Astronomy Club MIT WPU

Pune, India

India

NOAA-18

2025-06-06 12:07:00

Heidi Neilson

Gilboa, New York, United States

United States

NOAA-18

2025-06-06 11:46:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-18

2025-06-06 10:13:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-19

2025-06-06 13:03:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-18

2025-06-06 10:49:00

Cyprus Amateur Radio Society

Nicosia , Cyprus

Cyprus

NOAA-19

2025-06-06 10:14:00

Maufox

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-18

2025-06-06 11:32:00

Cosmos Astronomy Club MIT WPU

Pune, India

India

NOAA-18

2025-06-06 09:49:00

Oppressive Heat Project

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Cambodia

NOAA-19

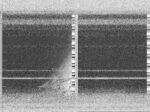

2025-06-05 19:25:00

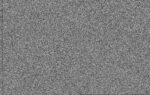

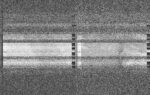

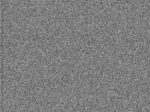

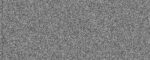

Zack Wettstein

Seattle, United States

United States

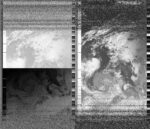

NOAA-15

It's only appropriate that just as the first heat wave strikes Seattle this summer, the life of 1 of only 3 remaining NOAA polar-orbiting satellites in operation has unexpectedly come to an end. Thanks to the unprecedented agency funding cuts in the current presidential administration, NOAA has ended support for this satellite program. While our skies are becoming smokier and hotter, we are losing more instruments to observe and document these changes. This image of static is the first pass decoded at the Seattle AGS after NOAA 18 was decommissioned. Rest in peaceful orbit...

2025-06-05 22:53:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-19

2025-06-05 20:22:00

Tsonami Arte Sonoro

Valparaiso, Chile

Chile

NOAA-15

2025-06-05 22:11:00

Goownown Growers

The Seaweed Institute

CAST, Helston, Cornwall, United Kingdom

United Kingdom

NOAA-19

2025-06-05 23:08:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-19

2025-06-05 22:59:00

Cosmos Astronomy Club MIT WPU

Pune, India

India

NOAA-18

2025-06-05 12:24:00

Filip Shatlan and Diana Engelmann

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-18

2025-06-05 12:20:00

Heidi Neilson

Gilboa, New York, United States

United States

NOAA-18

2025-06-05 11:59:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-18

2025-06-05 10:26:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-19

2025-06-05 09:13:00

Hospitalfield

Arbroath, Scotland

Scotland

NOAA-15

2025-06-05 11:02:00

Cyprus Amateur Radio Society

Nicosia , Cyprus

Cyprus

NOAA-19

2025-06-05 10:27:00

Maufox

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-18

2025-06-04 23:56:00

Filip Shatlan and Diana Engelmann

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-18

2025-06-04 23:06:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-19

2025-06-05 07:02:00

Oppressive Heat

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Cambodia

NOAA-15

2025-06-04 19:27:00

Heidi Neilson

Gilboa, New York, United States

United States

NOAA-15

2025-06-04 22:24:00

Goownown Growers

The Seaweed Institute

CAST, Helston, Cornwall, United Kingdom

United Kingdom

NOAA-19

2025-06-04 19:27:00

Hospitalfield

Arbroath, Scotland

Scotland

NOAA-15

2025-06-04 20:25:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-15

2025-06-04 11:23:00

Zack Wettstein

Seattle, United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-06-04 11:14:00

Tsonami Arte Sonoro

Valparaiso, Chile

Chile

NOAA-18

2025-06-04 21:24:00

Oppressive Heat

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Cambodia

NOAA-19

2025-06-04 10:39:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-19

2025-06-04 07:47:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-15

2025-06-04 10:40:00

Maufox

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-18

2025-06-04 08:26:00

Cyprus Amateur Radio Society

Nicosia , Cyprus

Cyprus

NOAA-15

2025-06-04 09:07:00

Maufox

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-19

2025-06-04 10:24:00

Cosmos Astronomy Club MIT WPU

Pune, India

India

NOAA-19

2025-06-04 08:01:00

Maufox

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-15

2025-06-04 06:20:00

Maufox

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-15

2025-06-03 23:13:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-18

2025-06-03 20:33:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-15

2025-06-03 22:43:00

Cyprus Amateur Radio Society

Nicosia , Cyprus

Cyprus

NOAA-18

2025-06-03 23:26:00

Maufox

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-18

2025-06-03 21:52:00

Maufox

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-19

2025-06-03 21:51:00

Cosmos Astronomy Club MIT WPU

Pune, India

India

NOAA-19

2025-06-03 08:54:00

Zack Wettstein

Seattle, United States

United States

NOAA-15

2025-06-03 08:33:00

Heidi Neilson

Gilboa, New York, United States

United States

NOAA-15

2025-06-03 18:58:00

Oppressive Heat

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Cambodia

NOAA-15

2025-06-03 12:39:00

Goownown Growers

The Seaweed Institute

CAST, Helston, Cornwall, United Kingdom

United Kingdom

NOAA-18

2025-06-03 12:36:00

Hospitalfield

Arbroath, Scotland

Scotland

NOAA-18

2025-06-03 12:08:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-19

2025-06-02 23:10:00

Zack Wettstein

Seattle, United States

United States

NOAA-18

2025-06-02 22:49:00

Filip Shatlan and Diana Engelmann

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-06-02 22:32:00

Tsonami Arte Sonoro

Valparaiso, Chile

Chile

NOAA-19

2025-06-02 23:32:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-19

2025-06-02 21:00:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-15

2025-06-02 22:56:00

Cyprus Amateur Radio Society

Nicosia , Cyprus

Cyprus

NOAA-18

2025-06-02 23:39:00

Maufox

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-18

2025-06-02 22:04:00

Cosmos Astronomy Club MIT WPU

Pune, India

India

NOAA-19

2025-06-02 11:25:00

Heidi Neilson

Gilboa, New York, United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-06-02 21:49:00

Oppressive Heat

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Cambodia

NOAA-19

2025-06-02 12:52:00

Goownown Growers

The Seaweed Institute

CAST, Helston, Cornwall, United Kingdom

United Kingdom

NOAA-18

2025-06-02 12:49:00

Hospitalfield

Arbroath, Scotland

Scotland

NOAA-18

2025-06-02 12:20:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-19

2025-06-01 22:58:00

Heidi Neilson

Gilboa, New York, United States

United States

NOAA-18

2025-06-01 23:39:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-18

2025-06-01 19:29:00

Zack Wettstein

Seattle, United States

United States

NOAA-15

2025-06-01 22:55:00

Hospitalfield

Arbroath, Scotland

Scotland

NOAA-18

2025-06-01 23:53:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-18

2025-06-01 23:52:00

Maufox

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-18

2025-06-01 23:51:00

Cosmos Astronomy Club MIT WPU

Pune, India

India

NOAA-18

2025-06-01 11:41:00

Filip Shatlan and Diana Engelmann

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-06-01 11:31:00

Goownown Growers

The Seaweed Institute

CAST, Helston, Cornwall, United Kingdom

United Kingdom

NOAA-19

2025-06-01 11:46:00

Cyprus Amateur Radio Society

Nicosia , Cyprus

Cyprus

NOAA-18

2025-05-31 22:02:00

Zack Wettstein

Seattle, United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-05-31 19:32:00

Heidi Neilson

Gilboa, New York, United States

United States

NOAA-15

2025-05-31 20:12:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-15

2025-06-01 00:05:00

Maufox

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-18

2025-05-31 20:30:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-15

2025-05-31 11:55:00

Filip Shatlan and Diana Engelmann

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-05-31 11:44:00

Goownown Growers

The Seaweed Institute

CAST, Helston, Cornwall, United Kingdom

United Kingdom

NOAA-19

2025-05-31 11:40:00

Hospitalfield

Arbroath, Scotland

Scotland

NOAA-19

2025-05-31 11:59:00

Cyprus Amateur Radio Society

Nicosia , Cyprus

Cyprus

NOAA-18

2025-05-30 22:15:00

Zack Wettstein

Seattle, United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-05-31 07:42:00

Cosmos Astronomy Club MIT WPU

Pune, India

India

NOAA-15

2025-05-30 23:21:00

Goownown Growers

The Seaweed Institute

CAST, Helston, Cornwall, United Kingdom

United Kingdom

NOAA-18

2025-05-30 22:00:00

Cyprus Amateur Radio Society

Nicosia , Cyprus

Cyprus

NOAA-19

2025-05-30 22:37:00

Maufox

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-18

2025-05-30 08:42:00

Filip Shatlan and Diana Engelmann

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-15

2025-05-30 08:37:00

Heidi Neilson

Gilboa, New York, United States

United States

NOAA-15

2025-05-30 08:18:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-15

2025-05-30 11:53:00

Hospitalfield

Arbroath, Scotland

Scotland

NOAA-19

2025-05-30 09:36:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-15

2025-05-30 11:22:00

Cosmos Astronomy Club MIT WPU

Pune, India

India

NOAA-18

2025-05-29 22:02:00

Heidi Neilson

Gilboa, New York, United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-05-29 22:42:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-19

2025-05-29 20:21:00

Filip Shatlan and Diana Engelmann

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-15

2025-05-29 21:04:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-15

2025-05-29 21:59:00

Hospitalfield

Arbroath, Scotland

Scotland

NOAA-19

2025-05-29 12:33:00

Zack Wettstein

Seattle, United States

United States

NOAA-18

2025-05-29 22:49:00

Maufox

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-18

2025-05-29 22:48:00

Cosmos Astronomy Club MIT WPU

Pune, India

India

NOAA-18

2025-05-29 11:50:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-18

2025-05-29 10:15:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-19

2025-05-29 13:05:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-18

2025-05-29 09:00:00

Goownown Growers

The Seaweed Institute

CAST, Helston, Cornwall, United Kingdom

United Kingdom

NOAA-15

2025-05-28 23:46:00

Filip Shatlan and Diana Engelmann

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-18

2025-05-28 19:34:00

Zack Wettstein

Seattle, United States

United States

NOAA-15

2025-05-28 22:15:00

Heidi Neilson

Gilboa, New York, United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-05-28 22:53:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-18

2025-05-28 21:31:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-15

2025-05-28 20:30:00

Tsonami Arte Sonoro

Valparaiso, Chile

Chile

NOAA-15

2025-05-28 19:51:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-15

2025-05-28 22:12:00

Goownown Growers

The Seaweed Institute

CAST, Helston, Cornwall, United Kingdom

United Kingdom

NOAA-19

2025-05-28 23:09:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-19

2025-05-28 23:02:00

Maufox

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-18

2025-05-28 19:10:00

Hospitalfield

Arbroath, Scotland

Scotland

NOAA-15

2025-05-28 23:02:00

Cosmos Astronomy Club MIT WPU

Pune, India

India

NOAA-18

2025-05-28 19:25:00

Cyprus Amateur Radio Society

Nicosia , Cyprus

Cyprus

NOAA-15

2025-05-28 10:28:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-19

2025-05-28 07:31:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-15

2025-05-27 23:42:00

Tsonami Arte Sonoro

Valparaiso, Chile

Chile

NOAA-18

2025-05-27 23:04:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-18

2025-05-28 07:13:00

Oppressive Heat

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Cambodia

NOAA-15

2025-05-27 19:37:00

Heidi Neilson

Gilboa, New York, United States

United States

NOAA-15

2025-05-27 20:17:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-15

2025-05-27 22:24:00

Goownown Growers

The Seaweed Institute

CAST, Helston, Cornwall, United Kingdom

United Kingdom

NOAA-19

2025-05-27 23:15:00

Maufox

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-18

2025-05-27 19:37:00

Hospitalfield

Arbroath, Scotland

Scotland

NOAA-15

2025-05-27 20:34:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-15

2025-05-27 11:23:00

Zack Wettstein

Seattle, United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-05-27 23:14:00

Cosmos Astronomy Club MIT WPU

Pune, India

India

NOAA-18

2025-05-27 21:26:00

Oppressive Heat

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Cambodia

NOAA-19

2025-05-27 10:40:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-19

2025-05-27 07:57:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-15

2025-05-26 23:56:00

Tsonami Arte Sonoro

Valparaiso, Chile

Chile

NOAA-18

2025-05-26 23:20:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-19

2025-05-26 23:16:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-18

2025-05-26 23:28:00

Maufox

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-18

2025-05-26 11:36:00

Zack Wettstein

Seattle, United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-05-26 11:13:00

Heidi Neilson

Gilboa, New York, United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-05-26 21:38:00

Oppressive Heat

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Cambodia

NOAA-19

2025-05-26 10:53:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-19

2025-05-26 12:42:00

Goownown Growers

The Seaweed Institute

CAST, Helston, Cornwall, United Kingdom

United Kingdom

NOAA-18

2025-05-26 12:39:00

Hospitalfield

Arbroath, Scotland

Scotland

NOAA-18

2025-05-26 08:23:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-15

2025-05-26 12:08:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-19

2025-05-25 23:13:00

Zack Wettstein

Seattle, United States

United States

NOAA-18

2025-05-25 22:49:00

Filip Shatlan and Diana Engelmann

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-05-25 22:48:00

Heidi Neilson

Gilboa, New York, United States

United States

NOAA-18

2025-05-25 23:33:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-19

2025-05-25 20:09:00

Tsonami Arte Sonoro

Valparaiso, Chile

Chile

NOAA-15

2025-05-25 21:09:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-15

2025-05-25 22:58:00

Cyprus Amateur Radio Society

Nicosia , Cyprus

Cyprus

NOAA-18

2025-05-25 23:41:00

Maufox

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-18

2025-05-25 22:04:00

Cosmos Astronomy Club MIT WPU

Pune, India

India

NOAA-19

2025-05-25 11:25:00

Heidi Neilson

Gilboa, New York, United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-05-25 11:01:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-18

2025-05-25 12:55:00

Goownown Growers

The Seaweed Institute

CAST, Helston, Cornwall, United Kingdom

United Kingdom

NOAA-18

2025-05-25 12:21:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-19

2025-05-25 09:01:00

Hospitalfield

Arbroath, Scotland

Scotland

NOAA-15

2025-05-25 10:37:00

Oppressive Heat

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Cambodia

NOAA-18

2025-05-24 23:00:00

Heidi Neilson

Gilboa, New York, United States

United States

NOAA-18

2025-05-24 23:41:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-18

2025-05-24 19:39:00

Zack Wettstein

Seattle, United States

United States

NOAA-15

2025-05-24 22:58:00

Hospitalfield

Arbroath, Scotland

Scotland

NOAA-18

A marked change in pressure. Cool breeze gone. Muggy close heat where before warmth from direct sun. Clear skies replaced by a full array of clouds. Low billowing cumulous and streaky mare's tails above. First rain last night, enough to just wet the ground. A deep inhale of the scent before bed. Train to Dundee along the coast in the morning, the haze is thick over the sea. Tensions run high. There's a far right rally in Dundee (and across Scotland) – well countered and outnumbered but more than anticipated. Union jacks and saltire flags, one that just says 'Jesus' and placards for Reform. They only have rage, we have joy on our side, songs and poems. Our chants ring across the square, louder. Refugees are welcome here. This is what community looks like. This is what solidarity looks like. The crowd breaks up as the student 'revel' begins, ceilidhing in costume as gods and stones and filling the square with messages of peace and love. Whose square? Our square. Crowded and sweaty train home, more factions and colours, but the fans are just happy and sunburnt in their red strips – Aberdeen won the cup.

2025-05-24 23:55:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-18

2025-05-24 23:55:00

Maufox

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-18

2025-05-24 19:30:00

Cyprus Amateur Radio Society

Nicosia , Cyprus

Cyprus

NOAA-15

2025-05-24 11:42:00

Filip Shatlan and Diana Engelmann

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-05-24 22:04:00

Oppressive Heat

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Cambodia

NOAA-19

2025-05-24 11:14:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-18

2025-05-24 07:36:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-15

2025-05-24 11:32:00

Goownown Growers

The Seaweed Institute

CAST, Helston, Cornwall, United Kingdom

United Kingdom

NOAA-19

2025-05-23 23:14:00

Heidi Neilson

Gilboa, New York, United States

United States

NOAA-18

2025-05-23 23:53:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-18

2025-05-23 20:22:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-15

2025-05-23 22:31:00

Maufox

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-19

2025-05-23 22:30:00

Cosmos Astronomy Club MIT WPU

Pune, India

India

NOAA-19

2025-05-23 11:55:00

Filip Shatlan and Diana Engelmann

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-05-23 11:27:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-18

2025-05-23 08:02:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-15

2025-05-23 11:44:00

Goownown Growers

The Seaweed Institute

CAST, Helston, Cornwall, United Kingdom

United Kingdom

NOAA-19

2025-05-23 11:41:00

Hospitalfield

Arbroath, Scotland

Scotland

NOAA-19

2025-05-23 12:02:00

Cyprus Amateur Radio Society

Nicosia , Cyprus

Cyprus

NOAA-18

2025-05-23 09:19:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-15

2025-05-22 22:15:00

Zack Wettstein

Seattle, United States

United States

NOAA-19

2025-05-22 20:48:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-15

2025-05-23 06:06:00

Oppressive Heat

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Cambodia

NOAA-15

2025-05-22 23:23:00

Goownown Growers

The Seaweed Institute

CAST, Helston, Cornwall, United Kingdom

United Kingdom

NOAA-18

Today we had to collect washed up seaweeds for a craft workshop on seaweed pressing. We love the pressing process as a way to engage people with seaweeds.

The day is perfect and I had more time than I usually do to collect. The seaweeds best for pressing are red seaweed that tend to grow at the bottom or below the intertidal zone. When they become dislodged from their holdfasts, dying, they wash up. A northerly wind blew from the land, making the nearshore water calm – it was bliss.

Over the last half a year we have been trying to learn a little how to interpret these beautiful satellite images of familiar landmasses and unfamiliar cloudmasses, not often sure what exactly we are looking at. One thing has been certain over the last few months- it’s been mostly warm and dry. We have seen many clear outlines of the cornish coast send down to us via audio file from the satellites.

It feels sadly fitting to have spent these months with our ground station, thinking more about weather, whilst the coast our work focuses on is current experiencing the warmest heat waves since records began.

Throughout April and May we have seen an ‘unprecedented’ marine heatwave in the northeastern Atlantic. The Met Office has described this heatwave as being unusual in its intensity and persistence.

The last time this was observed was in 2023, at the time the most severe marine heatwave recorded in this part of the ocean. Then, both Ruth and I were working harvesting seaweed at every low tide on The Lizard peninsular. Unaware of the data being gathered that summer, we anecdotally saw a large bleaching and dieback of our favourite seaweed Dulse. We worried about its recovery after this local marine heatwave and we wondered what data was being gathered on the effect of heat on the very shallow waters of the intertide. The Dulse seemed to recover well but we couldn’t help wonder how many of these events the ecosystem could withstand. Now working less physically close to this ecosystem, seeing more extreme marine heatwaves, we are left even more concerned for their future.

Today, whilst the tide is metres above most species, I swim in the unseasonably warm waters and gather dead floating seaweeds, a tool to teach people about the ecosystem. I wonder how many of them have died prematurely due to heat or if this is just the normal natural lifecycle.

2025-05-22 22:01:00

Cyprus Amateur Radio Society

Nicosia , Cyprus

Cyprus

NOAA-19

2025-05-22 22:39:00

Maufox

Mauritius, Mauritius

Mauritius

NOAA-18

2025-05-22 11:59:00

Heidi Neilson

Gilboa, New York, United States

United States

NOAA-18

2025-05-22 22:25:00

Oppressive Heat

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Cambodia

NOAA-18

2025-05-22 11:39:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-18

2025-05-22 10:03:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-19

2025-05-22 08:50:00

Filip Shatlan and Diana Engelmann

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-15

2025-05-22 08:28:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-15

2025-05-22 12:55:00

Foto Colectania

Hangar

Ràdio Web MACBA

Barcelona, Spain

Spain

NOAA-18

2025-05-22 11:53:00

Hospitalfield

Arbroath, Scotland

Scotland

NOAA-19

2025-05-21 23:36:00

Filip Shatlan and Diana Engelmann

Gainesville, Florida , United States

United States

NOAA-18

2025-05-21 21:14:00

Iterable pueyrredon

Cordoba , Argentina

Argentina

NOAA-15

2025-05-22 06:30:00

Oppressive Heat

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Cambodia

NOAA-15

2025-05-21 22:00:00

Hospitalfield

Arbroath, Scotland

Scotland

NOAA-19

I’ve been saying it’s not rained for a month for a while now. It must be longer. It gives me a sense of unease. Scorched grass. Arid dune-scapes. A feeling that there’s dust hanging in the air. The BBC reports the driest spring in 60 years. Getting frustrated by sprinklers on pristine university lawns, while there’s advice from Scottish Water to take short showers. According to SEPA my area has ‘moderate scarcity’ of water, one step below ‘significant’.