Local Date

3 November 2024Local Time

18:39Location

Petra Kočića Street, Banja LukaCountry or Territory

Bosnia and HerzegovinaContributor

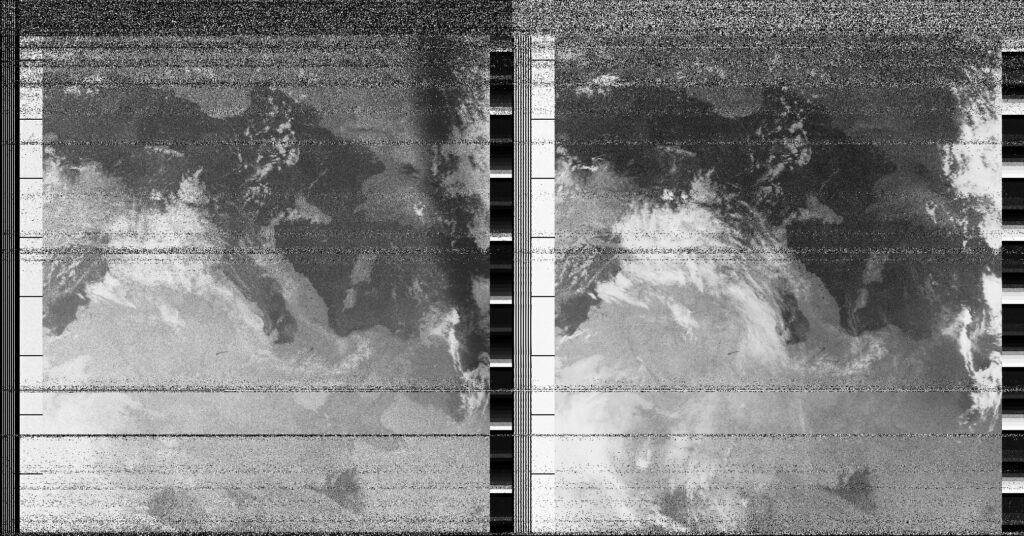

Sasha EngelmannSatellite

NOAA-15Radio Callsign

Archive ID

Coordinates

“Gdje je mala sreća, bljesak stakla, lastavičje gnjezdo, iz vrtića dah; gdje je kucaj zipke, što se makla, i na traku sunca zlatni kućni prah?” wrote Ivan Goran Kovačić in the poem Jama or ‘the pit’. It describes village life near the town of Jasenovac in modern day Croatia. In these lines, happiness flows through a ‘window’s glint’ and ‘windborne garden sweet’. It manifests ‘by the threshold, sunshine at my feet’. These lines evoke a bucolic, gentle, rural life. And yet the poem - immediately recognisable from these four lines by anyone borne in the Balkans - is far from a picture of happiness. It narrates what occurred at the town of Jasenovac after Axis forces invaded the Kingdom of Yugoslavia during WWII, and installed an Independent State of Croatia (NDH) ruled by the nationalist Ustaše militia. Jasenovac became the site of one of the deadliest forced labour and extermination camps of the war. What happened at the camp is disputed, but most evidence suggests that the majority of people imprisoned and executed at Jasenovac were ethnic-Serbs, largely civilians brought there for their collaboration with Partisan rebels. My grandfather, Deda Milan, was one of those anti-fascist Serbs brought to Jasenovac, but luckily he was released after my great grandmother, of Croatian / Hungarian heritage, managed to use her influence to save him. Roma, Jews, and political communists were also targeted. Kovačić’s poem goes on to narrate the horrors of Jasenovac in gruesome detail, and its power in communicating these scenes made it one of the most celebrated anti-war poems of its time. Most children educated in former Yugoslavia (and even, I learn at dinner in Banja Luka, in present day Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina) learn this poem in school. This context might help explain why the lines quoted at the beginning of this note - about happiness, gardens and sunny thresholds - are engraved in a plaque inside a large scale monument designed by Bogdan Bogdanović in the 1960s that now stands at the former centre of the Jasenovac camp. Its shape resembles a giant flower with six petals from some angles, but from others, it looks like a pair of wings. The edges of the petals are sharp, and diamond shaped holes allow the sky to shine through, against the heaviness of concrete. As I walked around it at sunset, its form seemed to transform, always asymmetrical. In the landscape around the monument, Bogdanović created mounds to denote the places where buildings of the camp used to stand. The monument was Bogdanović’s attempt to memorialise the history of civilian suffering without reproducing it, toward “termination of the inheritance of hatred that passes from generation to generation". To place lines of poetry depicting ‘sunny thresholds’ or ‘windblowne gardens’ at the heart of this monument is perhaps to use peaceful images - peaceful weathers - to break the ‘inheritance of hatred’ while recognising the importance of careful, watchful memory.